Short Foreword

I first came across Stefan Reinartz in FIFA 15. I found out that you could sign him for free, so I used him in almost every manager career I started. Then, I found Raphael Honigstein’s primer on ESPN. I was surprised – a FIFA 15 favourite of mine now an analyst? So naturally, I dug deep. But research was hard – while there was plenty of information online about Reinartz’s exploits as an analyst, there was little on him as a player. But thanks to transfermarkt.co.uk and German Wikipedia (and Google Translate), I was eventually able to unearth a massive amount of information. A shout-out to these sites and Raphael Honigstein! Many pieces, such as the top players under the Packing rating and Reinartz’s statements, have been taken from Honigstein’s article on ESPN.

Reinartz the Footballer

Injuries can wreck a player’s career. They prevented Diego Maradona from excelling at Barcelona, prevented Ronaldo, Alexandre Pato and many others from reaching greater heights, and literally destroyed once-promising players’ careers, like Stefan Reinartz’s.

But first, let’s skip back a beat. We are looking at a promising youngster named Stefan Reinartz, who can play as a defensive midfielder or as a centre-back. The German is very good at making interceptions and is adept at distribution. Soon, after playing with a couple of amateur clubs, he will toil his way through the Bayer Leverkusen youth academy system.

Reinartz started establishing himself as a reliable holding midfielder for the German youth national teams. He played regularly for the under-16 squad. He also represented his country at the 2006 under-17 European Championship, where Germany clinched 4th place. But even greater was his performance at the 2008 under-19 European Championship. He played all of the fixtures in that tournament and Germany won the trophy.

The breakthrough in his club career was the 2008-09 season, when he was on loan at the German 2.Bundesliga side Nurnberg. A month into the loan deal, on the 9th of February, 2009, Reinartz played his first professional match. The game was against Kaiserslautern. Kaiserslautern was thrashed 3-0. Reinartz and his (interim) teammates took Nurnberg to the top tier of the German Bundesliga.

Initially, Reinartz was supposed to be at Nurnberg till 2010. However, the newly-hired Bayer 04 gaffer Jupp Heyneckes, clearly impressed by Reinartz’s performances, forced a deal which brought Reinartz back to Bayer in the summer of 2009.

Reinartz immediately got his chance to shine for the Bayer Leverkusen senior team. He played against Babelsberg in the German Cup on the 31st of July, 2009. On 8 August 2009 Reinartz played his first game for Bayer in the Bundesliga against Mainz. The match ended 2-2. In November, the German scored the first goal of his senior career against Eintracht Frankfurt (a club whthirdich he would later play for) in a game that ended 4-0. Reinartz was beginning to become a regular starter for Bayer 04.

After playing in the qualifiers for the under-21 European Championship, Reinartz soon saw himself with the senior national side. However, Reinartz didn’t get played much, particularly because Germany had an even better defensive midfield player in Sami Khedira (who was subbed off to make way for Reinartz in the 72nd minute of a game against Malta in order to give Reinartz his first experience of playing for the senior national squad). The Bayer man only played three games in total for Germany.

By 2013, people at Bayer Leverkusen started to realize that Reinartz had great intellect; not only was he a good player, but he also knew the game very well. One sign of his intelligence, for instance, was that Reinartz had never been shown red in his career. Reinartz was made a second assistant manager for the Bayer 04 under-17 side. He also continued playing for the club at the same time.

Soon, though, Reinartz got some news that just popped right out of the blue. Bayer 04 chose to not renew his contract. A day before Bayer 04’s last match in the 2014-15 season Reinartz moved to Eintracht Frankfurt for the 2015-16 season, for free. He made nearly 150 appearances for Bayer and scored 11 during his time there.

On the 15th of August, 2015, Reinartz played his debut for Frankfurt. He scored in vain, as Wolfsburg beat Frankfurt 2-1. The 2015-16 season with Frankfurt proved to be terrible, even though Frankfurt escaped relegation. He played only 16 out of 34 games for the club. And out of those 18 missed matches, he only spent one match on the bench.

And the rest? You know the answer. To say that Reinartz was injury-prone would be an understatement. We have seen many injury-prone players before. Daniel Sturridge, Robin van Persie and Jack Wilshere, to name a few, have been tormented by injuries very often. But Reinartz lived in another planet of bearing injuries. Possibly a planet with bad playing surfaces and somewhere where all defenders idolize Andoni Goikoextea.

The reason for which Bayer Leverkusen didn’t offer a new contract to Reinartz was because his last few months at Bayer, in the 2014-15 season, were troubled by an orbit (eye socket) fracture. He missed 12 games because of the injury. The 2013-14 season at Bayer was also ruined with heel issues. He missed a total of 21 games that season. The 2015-16 season at Frankfurt turned out to be even worse. In November 2015, Reinartz faced issues with his patella tendon. He then missed the first three months of 2016 thanks to a groin operation. He caught the flu, had concerns with his hernia and ended the season with a hamstring injury.

Soon, Reinartz made the announcement. “My last three years as a footballer were marked by very many injuries and therefore disappointments too. After these last three injuries within the space of six months I no longer have that 100% conviction that carrying on is the best path for me in the coming years.” The Frankfurt player was born on the first day of 1989, which means at the time of retirement he was…27 years old?

A 27-year-old retiring. The average defensive midfielder reaches his prime only around 28-30. There have been a couple of prominent footballers who have retired around that age, like Stuart Holden, George Best and Brian Clough, but you don’t see such ephemeral careers every day, especially in this day and age. But Reinartz only retired in 2016.

“I will definitely remain connected to football,” he said. At that time, how he will ‘remain connected to football’ wasn’t mentioned.

Football didn’t hear anything of Reinartz for a month after his retirement. Until the European Championship of 2016.

Reinartz the Moneyballer

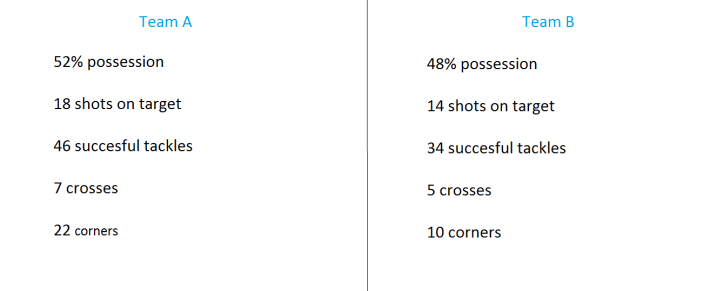

From a video by Reinartz’s consultancy agency, look at two teams and their corresponding statistics:

Who do you think won the match? (Clue: This is a historic match)

If you apply basic logic, Team A won. They had more possession, took more shots, won more corners and crossed more. They did tackle more, but that doesn’t matter as much. Whether tackles are good or not is still being debated. Team A’s win wouldn’t be too emphatic, since the stats look close. A 2-1, maybe?

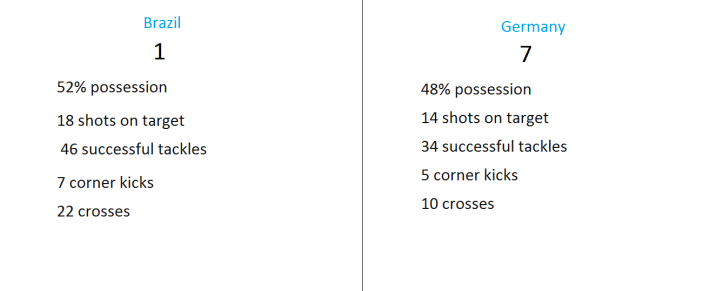

Now look at the same statistics, but now with the names of the teams added and the scoreline in there as well:

What? How’s that possible? Brazil dominated the stats and yet lost. And not just by any small margins. Six goals!

This just shows the unreliability of normal data when it comes to analytics. There are many such examples of this. The number of shots, passes, percentage of possession, percentage of passes completed, and number of crosses don’t translate to goals scored and conceded on the football ground.

“I always enjoyed thinking about numbers and probability models, but I really became interested in the field after hearing a lecture on football stats at the German Sports University in Cologne.” he told ESPN, “It discussed a study that showed that most common statistical numbers – possession, passing success rates, one-on-ones – had no relevance to the end result. So me and my [ex] teammate Jens Hegeler (who currently plays for Hertha Berlin) thought, ‘let’s see if we can do better.’”

In a world of tiki-taka and its replicas, passing is the most important thing in the world. However, passing is not the most important player action in analytics. And passing is used in attack. As Valeriy Lobanovskyi once said, it is easier to defend with all 11 players, rather than five or six. So doesn’t that mean it’s easier to attack with fewer players between you and the goal?

Passing and attacking are what matter to Reinartz and Hegeler. They assigned values for passing. Efficient passing, the German style. A good pass is one that takes an opposing defender ‘out of the game’, that is, getting past an opposing defender, leaving fewer defenders between you and the goal. Efficient passing or dribbling, that takes multiple opponents out of the game, is the best pass. So, Reinartz and Hegeler started counting the number of players taken out of the game by players in a match. They named this metric ‘Packing.’ A player with high Packing rates is obviously a good one. They also assigned higher rates for taking out defenders.

Both the player-analysts who designed the metric were defensive midfielders. For long, defence-minded players have been neglected by both traditionalist fans, managers and the rest and even armchair fans with an analytical bent. The Packing method of ranking defenders is by measuring the number of opposing attackers taken out of the game by a defender winning the ball. Defenders who can convert defence into attack are also valuable. Hence, we can also look at the number of a defender’s teammates brought into the game by the defender winning the ball.

But we can’t forget the big number 9! A winger can achieve high packing rates by dribbling well, a centre-midfielder can do so by passing well, and defenders can rank high by winning possession. What place does a ‘target man’ striker have in the Packing system?

A pass isn’t completed by the passer. Giving the ball to your teammate is one thing, but the pass has to be received by someone. Not just that, the receiver has to position himself in free spaces and gaps inside the opposition defence. He also has to time his run to perfection. For that reason, Reinartz and Hegeler also took into account the number of players taken out of the game by the receiver. “I believe the importance of attacking players as pass recipients is the greatest insight we have gathered over the last couple of years.”

Reinartz and Hegeler’s metric came under the spotlight in the Euro 2016. There, 66.6% of matches were won by the team with higher Packing rates. Only 6% of matches were lost by teams with a higher Packing score. Let Reinartz explain it to you: “The correlation between getting the ball past opponents and winning is between 0.3 and 0.4, with one being a 100 percent correlation. If you then drill down into the numbers of defenders that were taken out, the correlation rises to 0.6, which is statistically very significant.”

We know that Packing is a reliable metric. It was then put to practice for evaluating players.

Toni Kroos was by far the best passer. His Packing rate was 82 opposing players taken out of the game by passing. Graziano Pellè, the Italian target man who plays for Southampton, was the best pass recipient in the Euros, taking out an average of 82 players per game.

And who was the best player at the Euro? Antoine Griezmann (who also won the player of the tournament award). The Frenchman was the fifth-best dribbler and was also in the top 10 of best pass recipients. He scored six goals in the competition, too. So, Atlético Madrid, you have a gifted player on your books.

Arsène Wenger, the manager I hate and admire at the same time, will profit from his use of statistics to judge players. Granit Xhaka, the midfielder who was moved to Arsenal for €45 million, averaged 55 players taken out of the game per game. Xhaka alone in the Gunners’ midfield won’t be too effective, but if combined with a certain German playmaker, Arsenal may become one of the deadliest attacking units in the world. That German midfielder’s name is Mesut Özil.

Reinartz has the utmost respect for Özil. “Özil enables you to get the ball past players,” Reinartz said. “He’s the best in the world between the lines, which is why he’s an automatic starter under any coach even if the public don’t always appreciate him.” Just about every football watcher know how good he is in distributing the ball, but no one knew his skill in making runs and finding spaces. His Packing rate was 63 players per game taken out by receiving the ball.

Packing isn’t just limited to player evaluation, but we can use the metric for team evaluation. It can also analyze England’s exit from Europe – not the one in which the UK exited the European Union, but the one in which England lost the pre-quarter finals to Iceland. England took only 28 players out of the game, while Iceland took out 41. “England played without a sense for the dangerous spaces,” Reinartz said, “They took up positions on the pitch rather than positions in space. They constantly [had] to rely on athleticism and one-vs-one situations because their passing and positional game [wasn’t] good enough.” The classic English stereotype in which they are a team that only relies on physique and stamina was confirmed. That’s the biggest advance in knowledge in Germany: we produce players and coaches who understand the importance of space,” he added. Perhaps the England FA should have hired Guus Hiddink or Dirk Schuster, who know about the mainstream European game, instead of giving Big Sam the job.

Reinartz’s metric will be used a lot soon. It is already used by Borussia Dortmund and… Bayer Leverkusen. Bayer have let go of Jens Hegeler and Stefan Reinartz the players, but are currently using their analytics.

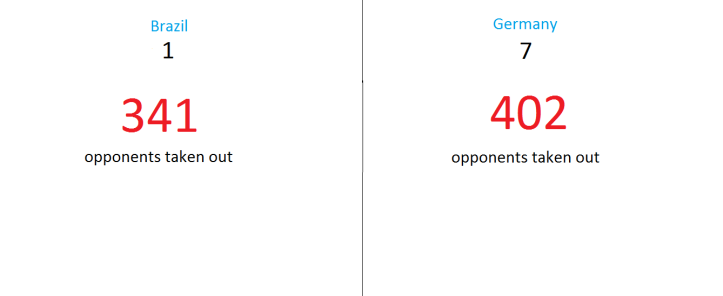

Let’s look at the Brazil-Germany match of the 2014 World Cup again, shall we? But this time, with Packing data:

Looks like an easy win for Germany, now doesn’t it?

Image Attribution

Featured Image: By Mathias Sichting – http://www.fluesterer.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10601529

Stefan Reinartz German line-up: By Mathias Sichting (FluestererMD) – Transferred from de.wikipedia to Commons.; (Original text: http://www.fluesterer.com (eigene Homepage)), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10593958

Mesut Ozil: By Anish Morarji from St Albans, England – Emirates Cup – Arsenal v Wolfsburg, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47232349

[…] first time I came across Granit Xhaka’s brilliance was when I was doing research for my post on Stefan Reinartz’s Packing metric. Xhaka took out 55 players per game in the European Championship of […]

LikeLike

[…] first time I came across Granit Xhaka’s brilliance was when I was doing research for my post on Stefan Reinartz’s Packing metric. Xhaka took out 55 players per game in the European Championship of […]

LikeLike